Crop Classification in Challenging Geographies

Interpreting agricultural landscapes

Accurate, in-season estimates of crop extent and yield would be useful to a variety of audiences including governments, development agencies, and various organizations along agricultural value chains. Ultimately, knowing where crops are and how well they are performing will be critical in the development of insurance and financial services products for small-scale agriculturalists in developing countries. Predicting where specific crops are being grown in a current growing season using satellite imagery presents many unique challenges. Unlike roads and buildings, a crop’s appearance changes throughout the year. Even with very high-resolution satellite imagery, it can be difficult to identify specific crop types by eye. The challenge is even greater in developing countries in which field sizes are generally small; even moderate-resolution satellites like Sentinel-2 (below) may not be able to distinguish individual field boundaries in certain regions.

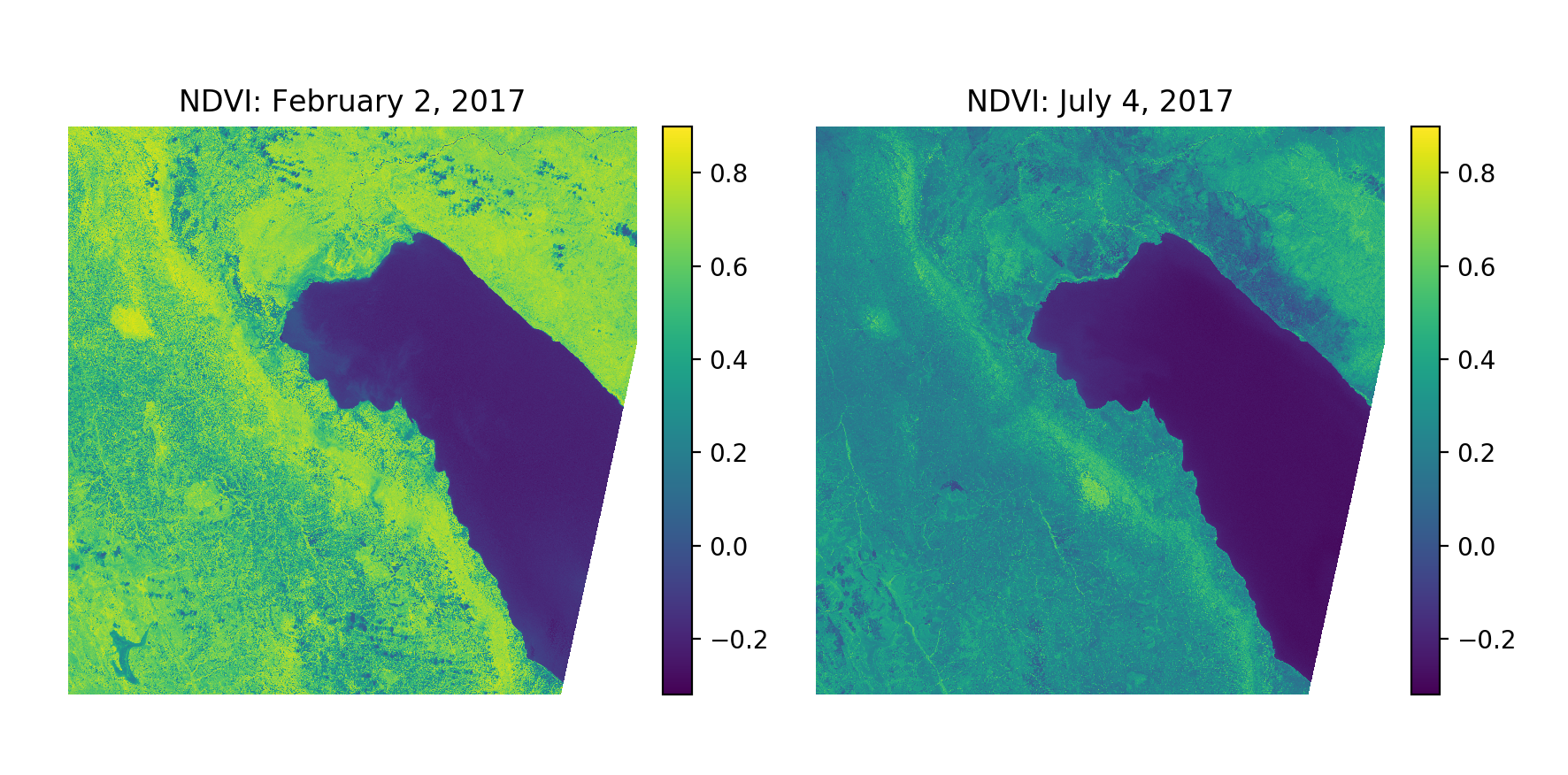

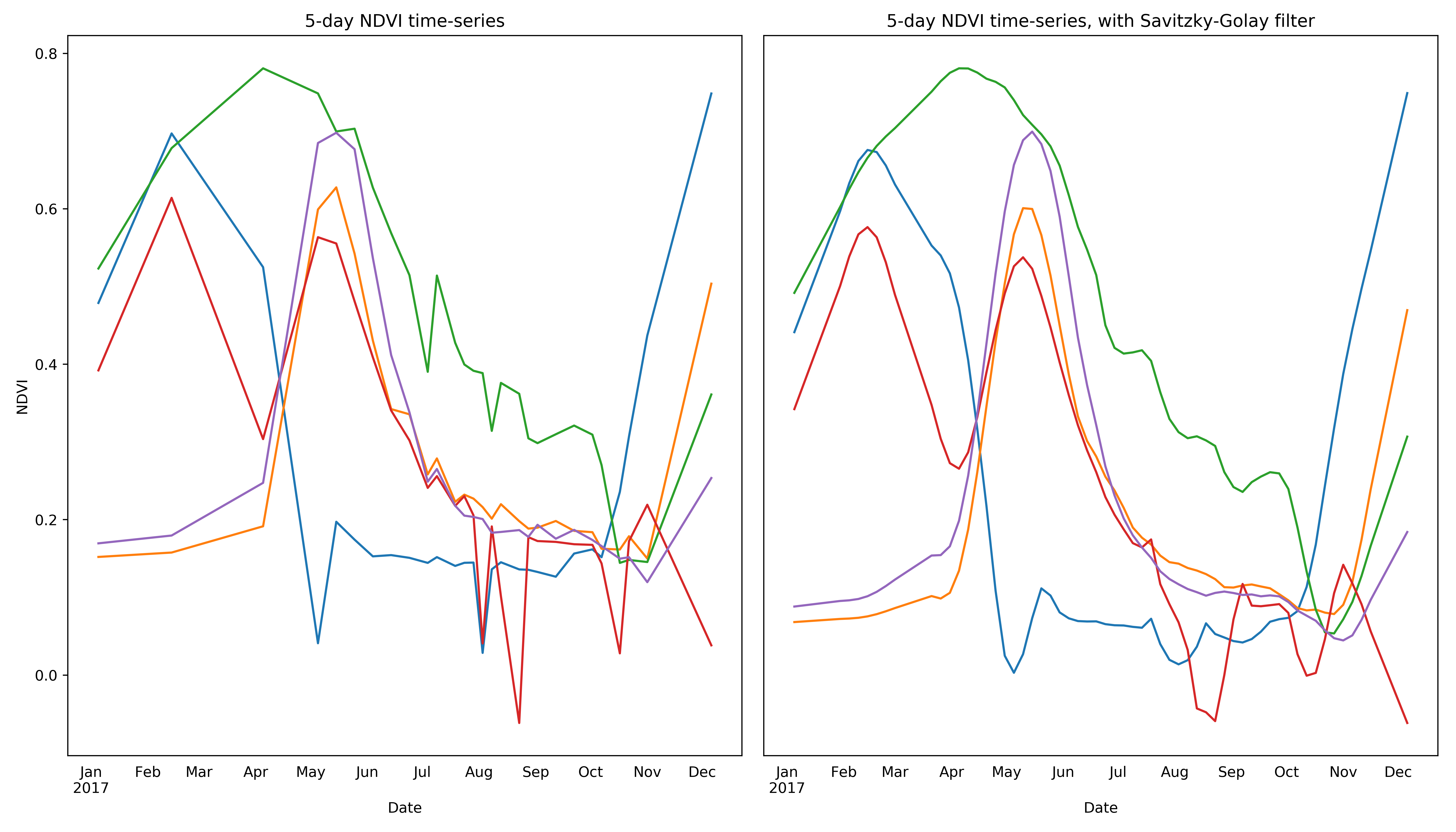

Using multi-spectral and multi-temporal information from satellite images makes it possible to distinguish individual crop types that may be difficult or impossible to identify by eye. As a concrete example, we can use information from the red and NIR bands of a Sentinel-2 tile to generate a new band for the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), a useful value for distinguishing vegetation from other land cover classes. As can be seen below, NDVI values for vegetated pixels (including cropped area) change over time, exhibiting distinct patterns based on the physiology of the plant(s) occupying a given pixel.

The general lack of ground-truth training data has also constrained the development of successful models for crop type classification in developing countries.

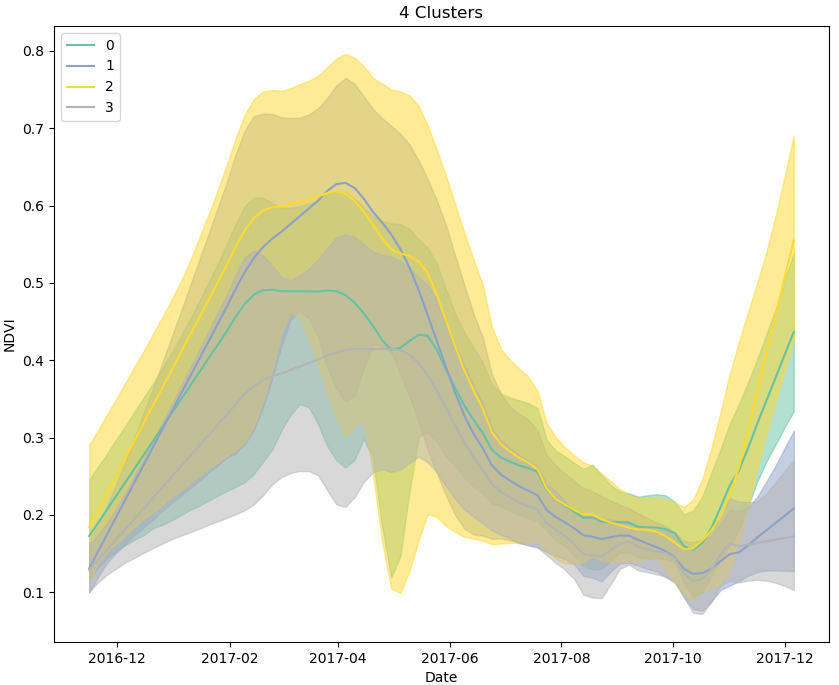

Using a clustering algorithm that takes the time-series of the input data into account when building a distance matrix (e.g. dynamic time warping), the pixels from the scene can be grouped together based on the shape of their NDVI curves for a growing season. The plot below shows the output of clustering 10,000 pixels designated as “cropped” area from the Sentinel-2 scene above, using K-means clustering (4 clusters) and dynamic type warping to generate a distance measurement between NDVI curves.

If, for example, we decide that pixels in clusters 0 and 2 most likely represent maize, based on their apparent planting and harvesting dates, and peak NDVI values, we can label them as such and generate thousands of semi-synthetic training data samples for use in supervised classification models, including models such as recurrent neural networks that explicitly leverage information captured in time-series’.